This is the 2nd in a series of articles looking at stitches and styles of needlework and how or if they fall within the time frame boundaries of our focus 600-1600 AD.

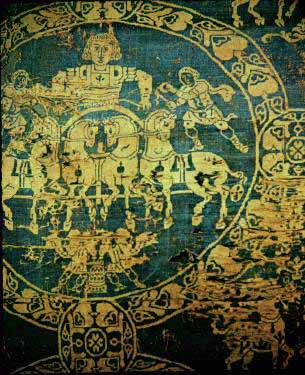

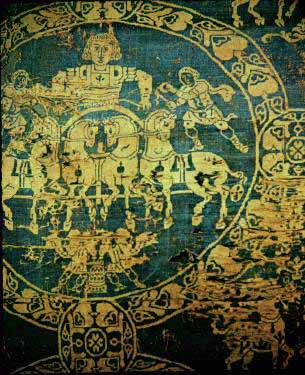

The concept of a "void" or absence of color or design has long been seen in a number of different cultures and in a number of different mediums. One obvious example comes  to mind with the Hellenic pottery and paintings (2500 1200 BC). The use of 2 colors red and black (the void) where one is the design and the other "color" sets off the design by its stark simplicity or absence. We see this concept in textiles in 6-8 C. AD in the Sassanid Empire and Byzantine Empire. Two such woven silk examples are a silk twill with a blue background and cream center design of a senmerv that was in the reliquary of Saint Len, Paris (London: Victoria and Albert Museum) and a silk serge with a blue background and cream center design of a charioteer found in Charlemagne's tomb, but was an import from the Byzantine court. (right - from Images from History: Image Archive)

to mind with the Hellenic pottery and paintings (2500 1200 BC). The use of 2 colors red and black (the void) where one is the design and the other "color" sets off the design by its stark simplicity or absence. We see this concept in textiles in 6-8 C. AD in the Sassanid Empire and Byzantine Empire. Two such woven silk examples are a silk twill with a blue background and cream center design of a senmerv that was in the reliquary of Saint Len, Paris (London: Victoria and Albert Museum) and a silk serge with a blue background and cream center design of a charioteer found in Charlemagne's tomb, but was an import from the Byzantine court. (right - from Images from History: Image Archive)

.

Assisi Embroidery: What is in a Name

Much of the terminology for stitches and techniques that we have today comes from Victorian times. The fashion magazines morphed into magazines with many articles on how to do all the things ladies of fashion were expected to know and do well. Magazines such as Godey's had articles on needlework and even published designs. There also was a rise in magazines that focused just on needlework and several dictionaries of needlework were published. Many of the naming conventions for stitches come from these publications.

In the late 1800's various parts of Italy were undergoing a recession. It was through the "good works" of the Contessa de Brazza that each area was urged to develop a different type of needlework for home industry and revive traditional handicrafts. In the area of Assisi, Maria Bartocci Rossi and her daughter Chiarini Rossi Buzi researched the old patterns of textiles that were owned by the "great" families of the area or were housed in the convents and sacristies. In the area of Assisi, the style of voided work embroidery became popularized with this movement and now voided work in general is frequently referred to as "Assisi Embroidery".

In several books from the turn of the century, voided work is also referred to as "Reserva". Subsequent descriptions use the phrase "in reserve" when referring to the absence of embroidery in the heart of the design when the surrounding ground fibers are covered.

Voided Work in the 13th and 14th Centuries

In the Victorian and Edwardian books on embroidery, they speak of the great textiles of the 13th and 14th Centuries from Assisi. They discuss the embroideries done by the nuns that are pictorial in nature, showing the life of St. Francis. It being St. Francis they are described as abundant with birds and animals. While there are many bands of voided work in various museums, none that I have found so far, have dates earlier than the 16th Century. Whether this is because is it impossible to tell the earlier embroidery from the later without the help of carbon dating or similar, whether none of the earlier embroidery has survived, or other reason, I can not say.

Voided Work in the 16th Century

A quick survey of some of the 16th Century items suggests some patterns in the design elements. The work seems to fall into primarily 2 categories pictorial usually scenes from or referenced to Biblical works and nature including fantastical creatures. The Biblical work is not surprising considering that much of the needlework in 16th Century Italy was either done for the Church or for use in the private chapels of great homes. Nor are the depictions of nature including fantastical creatures surprising as this was the era of the "Modelbuchen"- the pattern books that are flowing across the borders and the printing of the bestiaries which depicted wondrous creatures both real and mythical.

In 1523 the first pattern book, a collection of woodcut designs, was printed by Johann Schonesperger the Younger in Augsburg. What followed over the next hundred years was an explosion of pattern books that were printed and distributed all over Europe and Great Britain. Since copyright does not exist yet, the same or very similar patterns were disseminated in books by different printers. For example I have found the same pattern for birds in Quentel (1527), Basee (1568), Noury (1532), and Ostaus (1561).

Many of the patterns are general, in that they are not designed for use with a specific medium. Some are specifically for lace, but many can be used with or without adaptation for any counted or semi-counted, or patterned needlework. In addition, a number of the patterns can be used as is or in reverse (voided). There are patterns in each of the above mentioned books and in some others where the pattern is specifically shown with both the regular pattern lines and with the pattern voided. Mistress Katheryn Goodwyn, in her article "Stalking the Wild Assisi", notes one example where the pattern is shown on one page and the voided pattern on the facing page. The patterns are also designed so the pieces can be reversed. There are examples of both birds and rabbits with patterns showing the creatures facing each other in several of the books.

|

|

| Vinciolo pattern for "a Pelican in its Piety" (1587) |

Pelican in Piety done in Cross Stitch by Mistress Aja du Jardin |

Apropos Patterns, is a book specifically devoted to looking at the pattern books and then identifying work that is derived from the patterns. There are two16th Century examples (pg. 47 & 51) of voided work where there are two needlework pieces with different provenance and the pattern book reference can clearly be identified.

In the examples I have found*, it appears that voided work embroidery was used primarily on "household goods" and linens for the chapel. Thus, we see the embroidery on covers (table, bed, etc.), towels, and alter cloths. Whether it was used on other items, such as clothing, is unclear. Frequently all we have is the embroidery and not the original 16th or 17th C. article.

|

Angel - charted by Linn Skinner in the style of those shown in period pattern books and Italian linens, done in Long Arm Cross Stitch on 36ct Linen with single thread of red silk. |

Design Elements

Outline of the Voided Design In Scheutte (pl 327) there is an unfinished embroidery originating in Italy and dated mid 16th C. The design was transferred to the linen by running stitches in red silk in the upper band and green silk in the lower band. On the same page, a similar embroidery of the same era and pattern is completed. The pattern is "drawn" with running stitches and the background is filled with long arm cross stitch in red silk. Thus, it seems that sometimes the pattern was transferred via running stitches, or as shown in other pieces*, back stitch or double running. Some pieces, however, do not seem to have an inner outline. The sampler that is the source of our heartsease, is the only example that I have seen, with a dramatically different outline color in the 16th or 17th Centuries. In the 18th C. with the new flourishing Assisi Embroidery, a black outline became popular.

Filling Stitches It appears that a number of different stitches were used as the background stitches. After surveying the examples*, it appears in the 16th C that long arm cross stitch, pulled work, and double running were popular. As the form moved into the 17th C other forms of cross stitch Italian Cross Stitch, Greek Double Stitch, and plaited stitch appeared. While there is one late 17th C example of regular cross stitch with this technique, it was in the 18th C that regular cross stitch became the stitch of choice.

Color The traditional colors appear to be red (usually a scarlet red), green, blue, and yellow where there is surface embroidery. Pulled work or cut work appears to be done in white thread. The primary thread type is silk in most of Europe. In all the pieces, except the one we have chosen for the pattern page, the inner outline, when there is one, is the same color as the background color. For our pattern page, the original piece was done with a dark, possibly blue outline, and a red (faded to brown) ground color. It is also the only piece, which I have seen so far, specifically outlined outside the background in a separate color.

Edging One of the other elements is the outer edge design. Some pieces have one and others do not. Some of the patterns in the pattern books are shown in combination with other patterns. Whether this resulted in the edging patterns is speculation. It may have been pure practicality in that some pieces due to their use or amount of space covered needed to have edgings.

On several of the ones with religious themes, the edging is a related verse. On several that have specific content such as angels or leaves, the edging pattern appears to reflect the content. However, in some cases, the content of the edging pattern appears to have no relationship.

On the earlier pieces the edging fills the adjacent block of threads and is the same length (side to side) as the piece. The edging pattern is sometimes also a voided pattern. On the later pieces, 17th C, where it is not voided, it seems to fall into two styles leaves or double running scroll bits. Of the later, I have only found two 17th C examples. This type of little double running edging becomes popular in Victorian times in connection with voided work. However, it is also seen on other 17th C samplers as decorative bits in double running patterns for both bands and single design.

* An appendix of 16th and 17th Century Examples -- The Appendix includes source, description, country of origin, date information, stitches, thread, and type of edging design, if any. 42 examples are cited from 5 different books.

Working a Piece of Voided Embroidery: Practical Hints

One of the things I find enjoyable about voided work is the level of detail. My preference is thus, to choose a piece of higher count linen (36ct) when working a piece for my own pleasure. However, one of the nice things about this style of embroidery is its versatility. It works on most any even weave count and even graces a piece of 14ct Aida beautifully.

Using an outline stitch of some form works well as a design transfer method. The choice is whether to use a similar or contrasting color thread and whether to use a thick or thin line of stitching. For a more period flavor, outline with the same color thread as for the ground embroidery and use a running stitch, double running, or back stitch. I find that double running gives me a nice balance of transferring the level of detail in the pattern and not adding bulk to the piece. If I am working the ground in 2 threads, I sometimes use only one for the outline.

Next comes working the ground embroidery. There are 2 choices to make here (1) which stitch to use and (2) how many threads to use for coverage. The objective is to cover the ground sufficiently to accent the absence of color in the unworked or voided portion. Thus, choose a stitch that covers sufficiently. With this in mind, it is understandable why long arm cross stitch was such a favorite it covers very well. If you use compensating stitches at the edges of the design, you also eliminate the "spottiness" that sometimes detracts from the clean edges of the design. Be sure not to stitch over the outline stitch, but to use it to add to the clean edges of the design.

Choosing the number of threads to use, is also a question of coverage. At 36 count, a single thread covers quite well. For 25 ct, I use 2 threads to give the level of coverage that I like. With a lighter color thread or with petit cross stitch (over 1), 2 threads may not be needed

Whether or not you use an edging pattern is primarily effected by the type of item on which the embroidery is being worked. For example, a towel may need a wide border of embroidery. Thus, to cover the area, a pattern of wide embroidery may be appropriate and a narrow border of edging to give it a finished appearance. Also, consider whether the fabric needs an additional border, such as Italian Hem Stitching.

Whatever voided work embroidery you chose to do enjoy it. As embroidery, it gives a wonderfully finished look to "household" linens.

Bibliography:

Books & Periodicals

A Book of Old Embroidery, with Articles by A. F. Kendrick, Louisa F. Pesel, & E. W. Newberry, Edited by Geoffrey Holm, "The Studio", Ltd., Paris, New York, 1921.

A Pictorial History of Embroidery, by Marie Schuette and Sigrid Muller-Christensen, Published by Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1964

Apropos Patterns for Embroidery, Lace and Woven Textiles, by Margaret Abegg, Published by Schriften Der Abegg-Stiftung Bern, Im Verlag Stampfli & Cie AG Bern, 1978. 3-7272-9005-6.

Assisi Embroideries, Ed. Th. De Dillmont, Mulhouse, DMC Library, DMC Thread Co., Ltd. London. 1926.

Assisi Embroidery: Old Italian Cross-Stitch Designs, by Eva Maria Leszner, B.T. Batsford Ltd, London 1988. 0 7134 5595 0.

Assisi Embroidery: Technique and 42 Charted Designs, by Pamela Miller Ness, Dover Publications, New York, 1979. 0-486-23743-5.

Charted Folk Designs for Cross Stitch Embroidery: 278 Charts of Ancient Fold Embroideries From The Countries Along The Danube, Collected by Maria Foris, Edited by Andreas Foris, Translated and Introduced by Heinz Edgar Kiewe, Dover Publications, New York, 1975. 0-486-23191-7.

The Complete DMC Encyclopedia of Needlework, by Therese deDillmont, Published by Running Press, 1978.

Flowers of the Needle, Mistress Elspeth of Morven and Mistress Kathryn Goodwin, self published, 1985.

German Renaissance Patterns for Embroidery: A Facsimile Copy of Nicolas Bassees New Modelbuch of 1568, Introduction by Kathleen Epstein, Curious Works Press, 1994. 0-963331-4-3.

New Little Pattern Book by Peter Quentel Koln 1527/1529: A Facsimile of Hiersemauu's 1882 Reprint, published by Linn Skinner, 2001.

Old Italian Patterns for Linen Embroidery, Collected and Published by Frieda Lipperheide, Translated and Edited by Kathleen Epstein, Curious Works Press, 1996. 0-9633331-7-8

Patterns Embroidery: Early 16th Century, by Claude Nourry & Pierre de Saincte Louie, Lacis, 1999. 1-891656-3.

Renaissance Patterns for Lace Embroidery and Needlepoint: An Unabridged Facsimilie of the the "Singuliers et nouveaux pourtraicts" of 1587 by Frederico Vinciolo, Dover Publications, New York, 1971.0-486-22438-4.

"Ricami d' Assisi2: Una Fantasia Di Motivi Da Ricamare Con I Nostri Schema A Color", Editor Mani Di Fata, I Lavori Femminili, Sept. 1999.

Samplers From the Victoria and Albert Museum, Clare Browne and Jennifer Weardon, V&A Publications, 1999. 185177 309 6.

On the Web:

Images from History: image archive http://www.hp.uab.edu/image_archive/ebyzantine/

"Stalking the Wild Assisi" by Baroness Kathryn Goodwyn, OL

http://www.bayrose.org/wkneedle/assisi.html

Les Singvliers Et Novveaux Povr- traicts, Dv Seignevr Federic de Vinciolo Venitien, pour toutes sortes d'ouurages de Lingerie. -- 1606

http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/vinciolo/

to mind with the Hellenic pottery and paintings (2500 1200 BC). The use of 2 colors red and black (the void) where one is the design and the other "color" sets off the design by its stark simplicity or absence. We see this concept in textiles in 6-8 C. AD in the Sassanid Empire and Byzantine Empire. Two such woven silk examples are a silk twill with a blue background and cream center design of a senmerv that was in the reliquary of Saint Len, Paris (London: Victoria and Albert Museum) and a silk serge with a blue background and cream center design of a charioteer found in Charlemagne's tomb, but was an import from the Byzantine court. (right - from Images from History: Image Archive)

to mind with the Hellenic pottery and paintings (2500 1200 BC). The use of 2 colors red and black (the void) where one is the design and the other "color" sets off the design by its stark simplicity or absence. We see this concept in textiles in 6-8 C. AD in the Sassanid Empire and Byzantine Empire. Two such woven silk examples are a silk twill with a blue background and cream center design of a senmerv that was in the reliquary of Saint Len, Paris (London: Victoria and Albert Museum) and a silk serge with a blue background and cream center design of a charioteer found in Charlemagne's tomb, but was an import from the Byzantine court. (right - from Images from History: Image Archive)